Cognitive biases are errors in the ways we make decisions and judgments. They’re famous in the world of gambling, where players who are faced with uncertainty sometimes blow on dice for “good luck” and bet on black because the roulette ball has hit red 10 times in a row. But these frailties of human decision-making aren’t confined to casinos. They affect all of us, all the time, especially when our egos are on the line.

We surveyed 1,013 men and women to explore the ways our brains use faulty evidence and wishful thinking when we date and mate, from overestimating our sexual prowess to making snap judgments about the sex lives of others.

From Wikipedia’s list of nearly 200 biases, we shortlisted seven that have the potential to lead our logic astray in sex and relationships.

Jump to the findings that tickle your fancy.

- Egocentric bias – Men overestimate their penis length by an inch

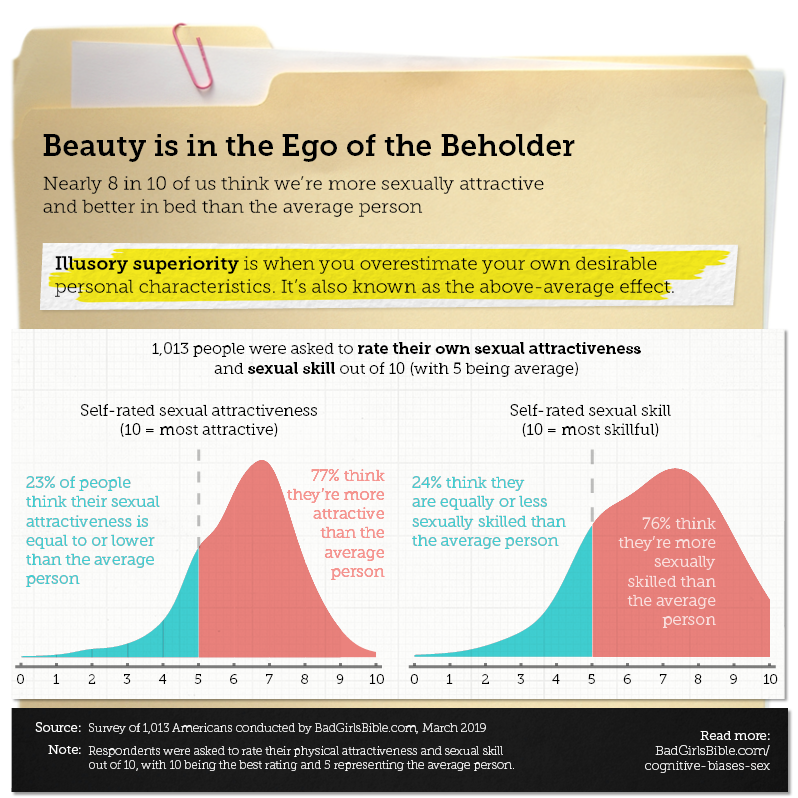

- Illusory superiority – Three-quarters of us think we’re better in bed than average

- The halo & horn effects – We assume better-looking people have fewer STDs

- Stereotyping – We judge each other’s sexual preferences based only on faces

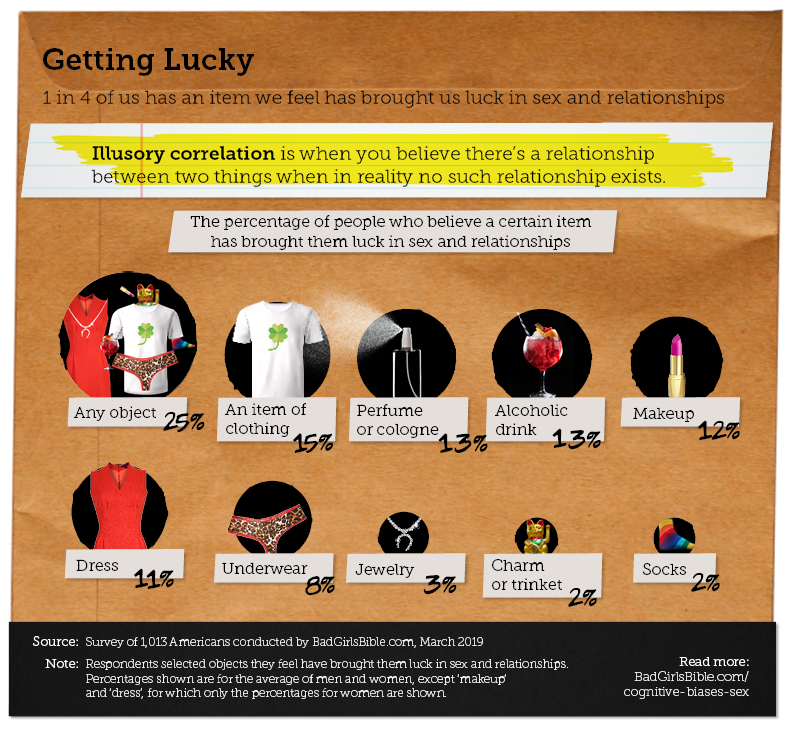

- Illusory correlation – 1 in 4 has an object they believe brings them luck in love

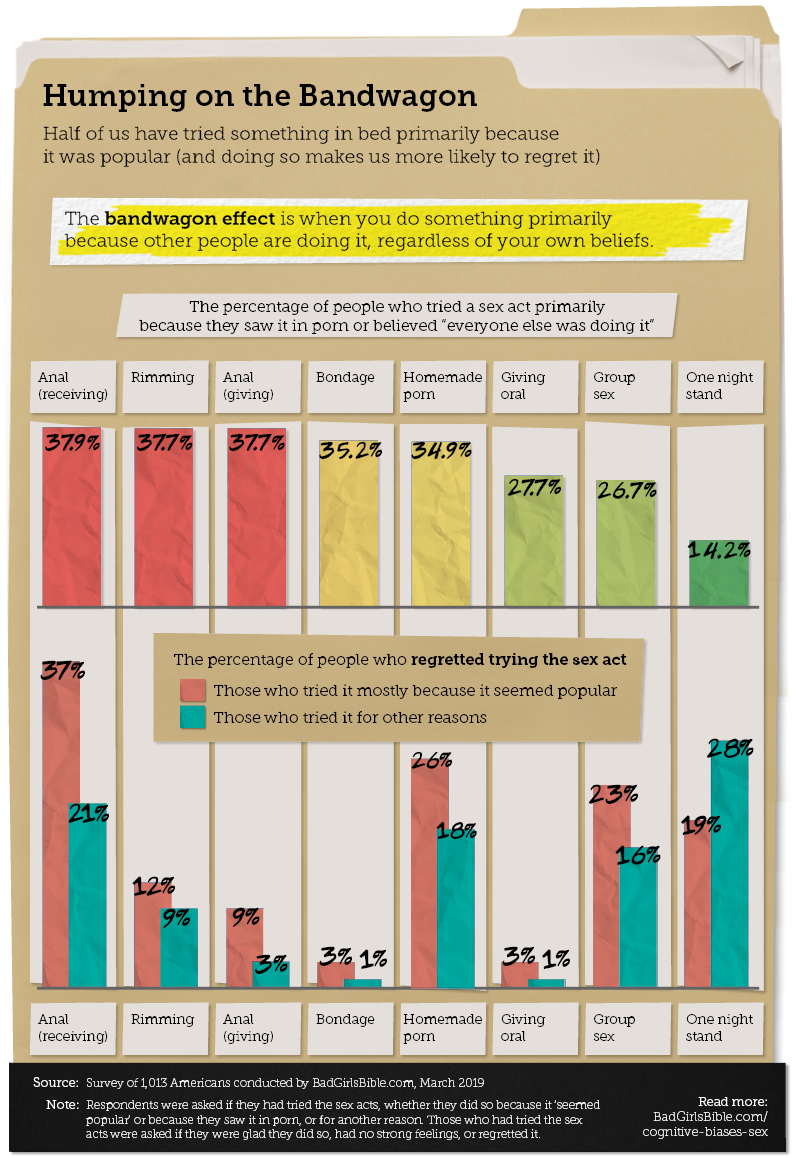

- The bandwagon effect – Half of people have tried a sex act because it’s popular

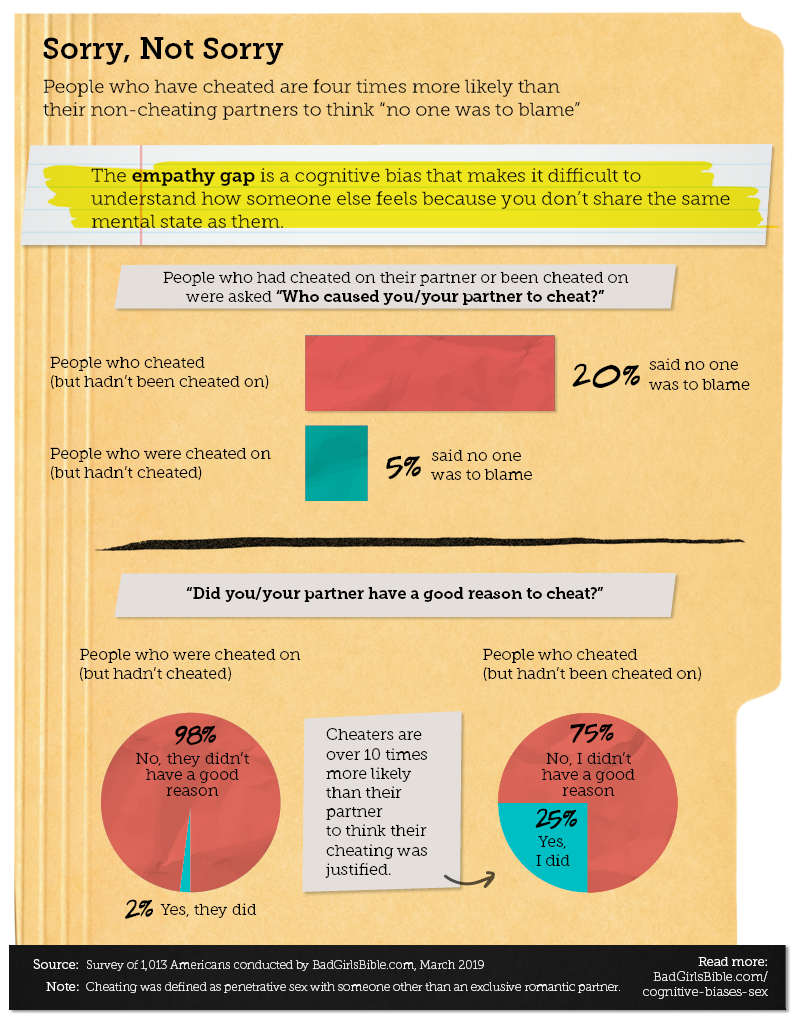

- The empathy gap – Cheaters are 4x more likely than non-cheaters to say their behavior was blameless

- Summary

- Methodology – who we surveyed and how we avoided bias

1. Egocentric bias – how we overestimate penis size

The egocentric bias, or self-centered bias, is when we put ourselves in a favorable light to protect our self-esteem. To test it, we asked a series of questions about the body part that arguably has more ego surrounding it than any other: the penis.

To find out if men misperceive the size of their penises, we asked them to estimate their erect penis length and take a guess at the same figure for the average man. In theory, and without the egocentric bias at play, the two average figures should have matched. Of course, they didn’t.

The average man said his erect penis was 6.22” (158 mm) but guessed the average of other men at 5.67” (144 mm). In other words, men typically think their penis is just over half an inch longer than the average penis.

Women also appear to be affected by the egocentric bias when estimating penis size. They put the average man’s penis length at 5.55” (141 mm), but their best guess for their most recent sexual partner was 0.67” longer, at 6.22” (the same as men’s average estimate for themselves).

In reality, the average erect penis length according to measurements of over 15,000 men is 5.16” (131 mm) – just over 1” shorter than the self-reported penis length of those we surveyed.

According to a study published in the Journal of Men & Masculinity, only 55% of men were satisfied with their penis size, with 45% wishing theirs was larger. Perhaps this is why so many men we spoke to gave themselves the benefit of an extra half-inch.

In contrast, 84% of women said they were satisfied with their partner’s penis size, and in a separate study, they said penis girth was more integral to pleasure than length.

Nevertheless, the male obsession with size holds strong, even driving some to seek penis enlargement surgery (the majority of whom fall into the ‘normal’ size category). There is currently no scientifically backed method for getting a bigger penis.

There’s some evidence to suggest that men with larger penises are more confident, typically rating their facial and body attractiveness higher than men of a smaller size. Our results back up this theory. On average, men who self-rated their sexual attractiveness between 8 and 10 on a 10-point scale estimated their penis length at 6.77” (172 mm), compared to 6.11” (155 mm) for men who rated themselves 5 to 7.5.

It’s not clear whether men think they’re more attractive because they have bigger penises, or imagine themselves to have bigger penises because they believe they’re attractive.

But what we do know is that cognitive biases and perceptions of attractiveness are frequent bedfellows.

2. Illusory superiority – how we assume we’re better than average in bed

If 5 is average, what would you rate your sexual attractiveness out of 10? On average, women who were asked this question rated their looks 6.2, compared to 6.4 for men. While these figures sound fairly modest, when the results are graphed, an obvious bias emerges.

77% of people rated themselves better looking than the average person – a statistical impossibility.

An almost identical proportion (76%) rated their sexual skill as higher than the average person. On average, men scored themselves 7.0, while women said 6.6. Members of both sexes who were less confident with their looks rated their sexual skill lower than those who considered themselves more attractive.

Research has demonstrated this bias, called illusory superiority, or the above-average effect, in other aspects of our lives as far back as the ’70s and ’80s. One study showed that 93% of drivers believed themselves to be more skillful than the average driver. And another revealed that over 90% of college professors rated themselves as above-average teachers.

When considering traits that form the scaffolding of our self-esteem, it seems most of us can’t bear the thought of being average. As we saw with penis size, when asked to rate ourselves relative to others, we typically don’t say we’re the best, but we do tend to give ourselves a bit more than we deserve.

How about when we turn our attention to other people’s looks – are we able to keep our biases buttoned-down?

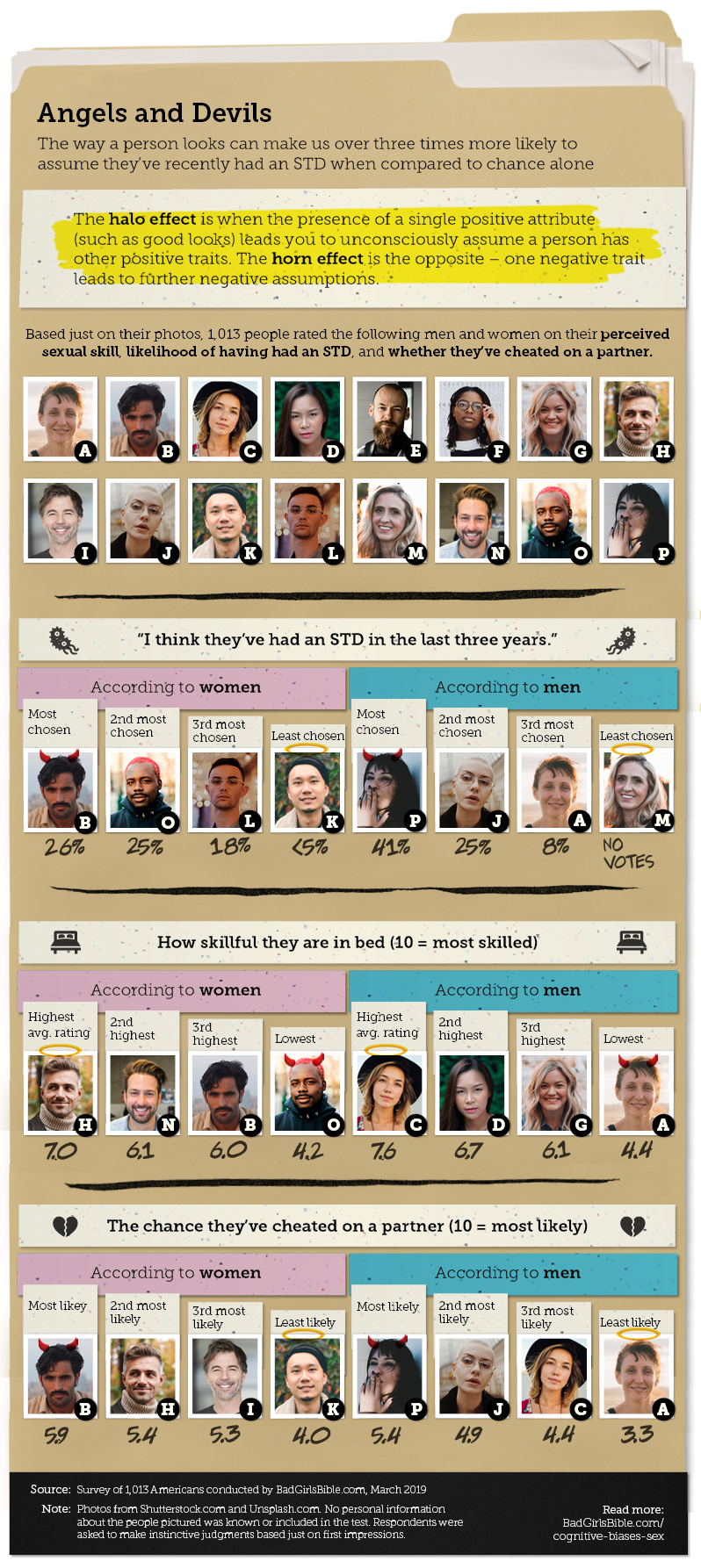

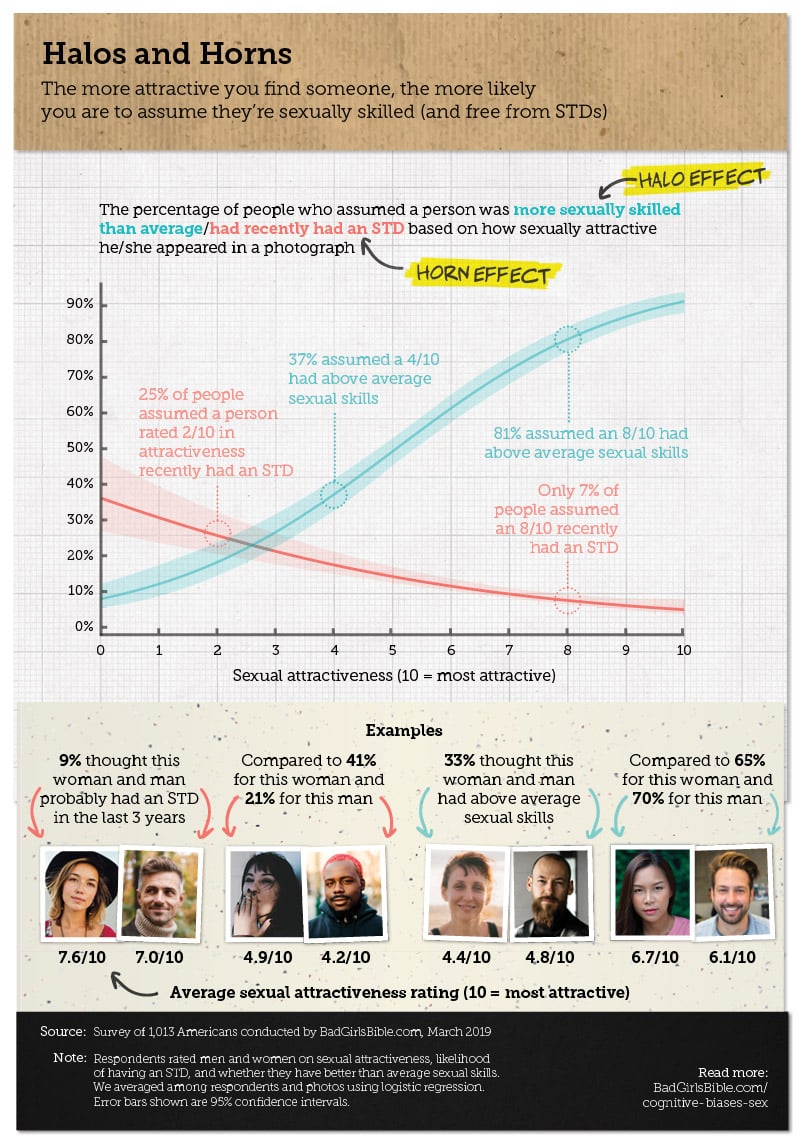

3. The halo and horn effect – how we give beautiful people the benefit of the doubt

In 1920, psychologist Edward Thorndike coined the term “the halo effect” to label a bias he’d observed in commanding officers when they were asked to evaluate soldiers. He noticed that soldiers with good physiques were rated more highly on intelligence, leadership, and character. One positive trait was causing the observer to assume they had other positive traits – in effect, they had a halo.

Since then, the bias has been demonstrated in many contexts, and it’s often physical attractiveness that gives subjects a “halo.” Better looking people are assumed to be happier, kinder, more successful, and even better parents.

The opposite is the horn effect – when the presence of a negative trait causes the observer to assume the person has other pitfalls.

To test the halo and horn effects, we selected 16 stock photos of male and female faces covering a range of appearances and levels of attractiveness.

Respondents were shown one of the faces at random (men were shown women and women were shown men) and asked to:

- rate their attractiveness

- say whether they thought they’d recently had an STD

- rate their sexual skill

- rate the likelihood of them having ever cheated on a romantic partner

To be clear, all they were shown was a photo – nothing personal about the people in the photos was known and respondents were asked to make snap decisions based on their first impressions.

Sexual skill was used to explore the halo effect, as being skillful in bed is a positive trait, while a history of STDs and infidelity represented negative traits.

STDs and the horn effect

If respondents made no assumptions based on the faces in the photos and instead chose at random, each picture would have received an equal share of the vote (12.5%).

In fact, when asked to point out the person they thought was most likely to have recently had an STD, 41% of men chose the same woman (P). Something about her appearance, perhaps her dark hair or the fact that she was the only woman smoking a cigarette, compelled 4 in 10 men to select her.

Women’s votes were more evenly spread across the men’s photos, but photo B nevertheless received 1 in 4 votes, compared to less than 1 in 20 for the least chosen man (K).

Sexual skill and the halo effect

The man rated most attractive by women (H) was also judged to be the most skillful in bed, while the least attractive was also selected as the least skillful (O). The same was true among men, who rated the woman in photo H as the most skillful and the most attractive.

The woman chosen by the men as least attractive was also deemed least sexually skilled on average. This might sound like an obvious result, as more attractive people are generally more appealing sexual partners. But we specifically asked about sexual skill. At best, respondents assumed more attractive people were more sexually experienced and therefore more skillful. At worst, they simply assumed less good looking people are worse in bed.

Cheating and the horn effect

The positive or negative characteristics of infidelity are less clear-cut than sexual skill and STDs. An attractive person could be considered more likely to cheat because they have more options, or less likely because they’re expected to have positive social traits. This is exactly what we saw in our results. The man in photo B was chosen most by women for recently having an STD and for having cheated on a partner. The same was true among men, who chose the dark-haired smoker in photo P for both. So far, negative is paired with negative (horn effect).

But second place among female respondents for likelihood of cheating was photo H, the man rated most good-looking by women. And among men, in third place was the woman rated most attractive (C). So cheating was also paired with attractiveness (negative with positive).

Previous research has shown that men believe more attractive women are more promiscuous, which could explain why the most attractive woman was voted third most likely to have cheated. Research has also shown that the more attractive a man considers a woman to be, the less inclined he is to want to use a condom when they have sex, which shows the real-world repercussions of letting cognitive biases control our urges.

To more clearly show the relationship between sexual attractiveness and positive and negative sexual traits, we averaged and graphed the ratings across all photos and respondents.

The more attractive a person is, the less likely we are to assume they’ve had an STD and more likely to think they’re more sexually skilled than average. For example, 9% of men thought a woman rated 7.6/10 recently had an STD, compared to 41% for a woman rated 4.9.

33% of women thought a man rated 4.8 had above-average sex skills, compared to 70% for a man rated 6.1.

“Facial profiling” is something we all do every day. In fact, it only takes one-tenth of a second for us to judge someone’s appearance and form a first impression of them. In the past, most judgments based on looks could quickly be updated by other facts gleaned through conversation, but with more of us using dating apps to judge each other based on looks alone, there’s more of a chance we’ll label someone in a way they don’t deserve, favorably or otherwise.

What about characteristics that are more ambiguous than STDs or sexual skill? Do we feel we can put something as abstract as a sexual fetish to a face or is that a psychological step too far?

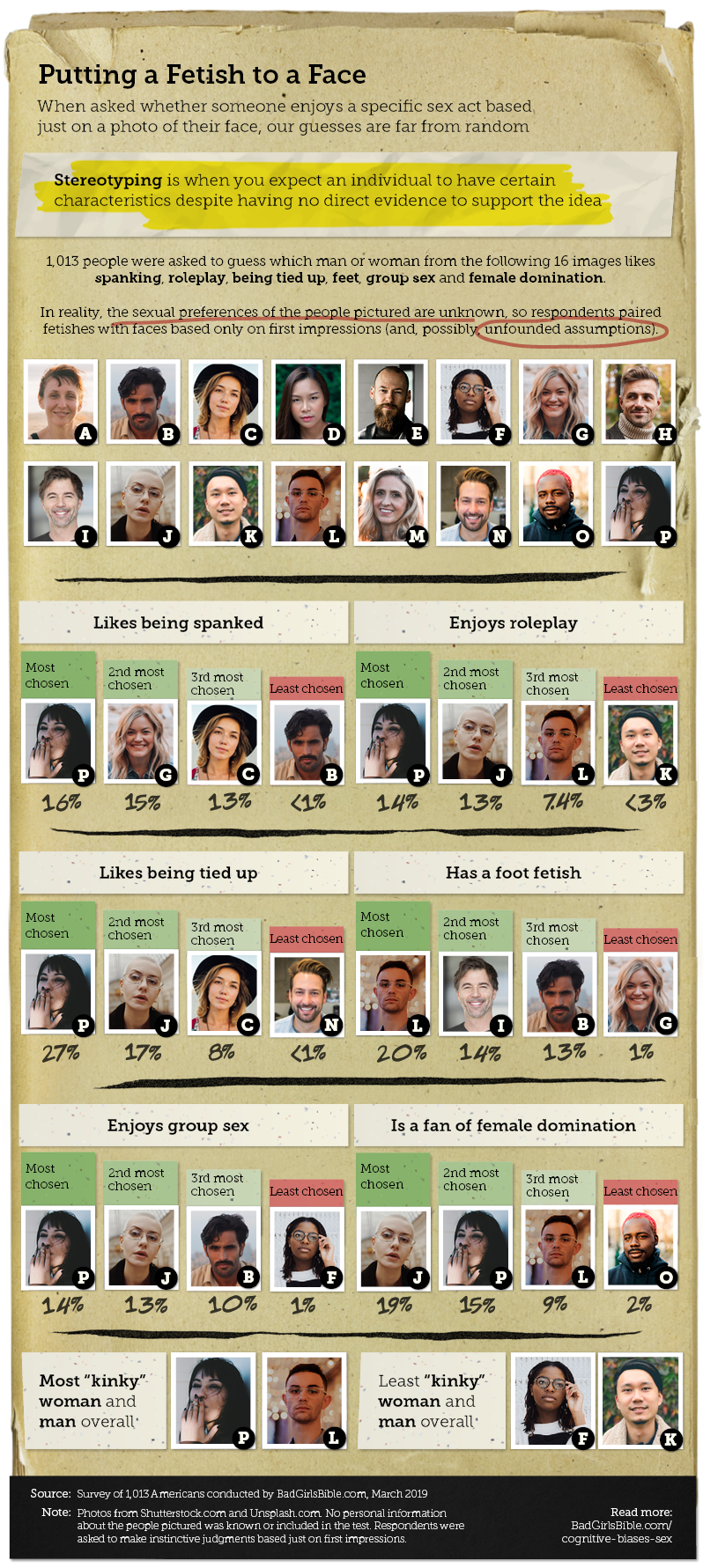

4. Stereotyping – how we silently judge each other’s sexual preferences

The same 16 faces used to test the halo and horn effects were also used to explore stereotyping more broadly, except this time our 1,013 respondents were shown the full grid of 16 faces instead of one selected at random. From the grid of 16, they were asked to choose the man or woman they thought was most likely to enjoy specific sexual fetishes and activities, including being spanked and female domination. They were free to choose the same person more than once if they wished or switch their choice every time.

As before, nothing about the sex lives of the men and women in the photos was known. If survey takers showed no bias when assigning the fetishes to faces, each person would have received 6.25% of the vote. However, stereotyping came into play.

In fact, the dark-haired smoker in photo P was chosen as most likely to enjoy four of the six fetishes. Sixteen percent of people thought she, more than any other person pictured, enjoyed being spanked – 2.5 times more than you’d expect by chance alone. For being tied up in bondage, she was chosen more than four times more often than chance.

The woman in photo J, with short blonde hair and distinctive glasses, received the most votes for female domination and was second highest behind P for enjoying erotic role play, being tied up and group sex.

What differentiates P and J from the other women? Perhaps their rebellious sense of style led people to think they’re more likely to have deviant sexual fetishes. However, according to research published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine, being spanked or whipped during sex is a sexual fantasy held by 36.3% of women, and 64.6% like the idea of being submissive to their dominant partner in bed. Furthermore, more than half like the idea of being tied up. Therefore these fetishes aren’t especially rare or deviant.

With little information to go on, people seem to have opted for the more unusual-looking individuals, or the extreme ends of the scale, despite the fact that many of our survey takers presumably enjoy several of the fetishes themselves.

Some stereotypes, or “empirical generalizations,” as they’re known in the scientific literature, are true. For example, “men are taller than women.” But only on average – there are lots of men who are shorter than women. It’s therefore surprising that so many people felt drawn to specific individuals’ photos over others.

Generally speaking, women were selected more often than men (even by women), except for “foot fetish,” for which the man in photo L received 1 in 5 votes – over three times more than you’d expect by chance.

5. Illusory correlation – how we believe inanimate objects bring us luck in love

1 in 4 of us owns an object that we feel has brought us luck in sex or relationships. Most of the time (15%), it’s an item of clothing such as a dress (11%) or underwear (8%). But 2% of us believe wearing a certain pair of socks will make the sex gods smile on us. There’s some evidence to suggest that wearing socks during sex makes us more likely to have an orgasm, so perhaps they could prove lucky.

13% of people feel a particular drink brings them good luck when dating, which could be considered a type of self-fulfilling prophecy. If we assume we’ll do better after having our lucky cocktail, or spraying our favorite perfume, we just might. (Other side effects of alcohol may also help us feel more confident and sexy.)

Lucky charms seem pretty harmless – there’s little risk if they don’t work. But some external influences, unlike lucky charms, might encourage us to do something we might otherwise have avoided.

6. The bandwagon effect – how “everyone else is doing it” makes us do it too

The bandwagon effect is when people align themselves with a product, person or idea purely because it’s popular. The effect can be seen in politics, fashion, sport and, according to our results, even sex. We asked people if they’d ever tried a sex act primarily because they’d seen it in porn or believed that “everyone else was doing it.”

Of the eight sex acts we asked about, anal sex (receiving) was most associated with the bandwagon effect, as 37.9% of people who had tried it said they’d done so mainly because they saw it in porn or believed everyone else was doing it. While the majority of women (56%) said they hadn’t tried it, it’s true that anal sex has become a lot more popular in recent years. A survey from 2010 found that 40% of women aged 20 to 24 had tried anal sex, up from 16% in 1992.

Rimming and giving anal sex were tried because of their perceived popularity by an almost identical proportion of people as receiving anal (37.7%), while group sex (26.7%) and one night stands (14.2%) were more resistant to the bandwagon effect.

The bandwagon effect isn’t always a bad thing. Checking critical reviews or noticing a thriving online conversation can be great ways to choose your next novel or a movie to see at the weekend. The only problem is when the book or movie sucks. In the case of sex, we measured this by asking the people who tried the eight sex acts whether they regretted the experience.

For seven of the eight sex acts, the people who tried them because of the popularity of the sex act were more likely to have regret than those who tried them for other reasons.

On average, we regret 13% of the sex acts we try because they’re popular, but the frequency of regret differs greatly by the act in question, ranging from 3% for giving oral sex to 37% for receiving anal.

These results remind us of the importance of trying new things in bed for sexual pleasure, not due to social pressure, whether it’s from a partner, society or porn.

There’s another facet of sexual regret that’s affected by at least one cognitive bias, and this time it doesn’t involve our (official) romantic partner.

7. The empathy gap – how we misperceive the causes of our infidelity

It’s one thing to overestimate our sex skills, consider ourselves more attractive than we really are, or even misjudge someone’s sexual preferences in the privacy of our own minds. It’s quite another when a cognitive bias clouds our perception of a sexual misdeed that can hurt our partners.

Infidelity is a prime example. In a cheater’s mind, there could be a dozen different reasons for their fling, but you can almost guarantee those reasons and their validity won’t be perceived in the same way by the person they’re cheating on. That difference can be described as an empathy gap.

24% of people admitted to cheating on a partner by having sex with another person, while 19% said they’d been cheated on in the same way. There’s a discrepancy there that suggests some of us are blissfully unaware of our partners’ misdeeds, but that’s not what we’re interested in here.

We wanted to know who gets the blame for cheating in the minds of those who cheat and those who are cheated on.

It turns out that 1 in 5 cheaters thought no one was to blame for their disloyalty (not even themselves), compared to only 1 in 20 victims of cheating. Put another way, 2% of people who had been cheated on said their partner had a good reason to cheat, compared to 25% of the partners who cheated.

A “good reason” in the mind of the unfaithful person might be that they’ve fallen out of love with their partner, whereas their partner may be unable to identify any reason, let alone a good one.

Even if they did know the full thought process behind their partner’s infidelity, they may not think their reasoning is good, because it wasn’t good for them. This is an empathy gap in action – one person fails to understand how the other feels because their mental state is completely different to theirs.

Summary

It was surprisingly easy to demonstrate seven ways cognitive biases skew our sexual thinking, mostly because of how universal and dominant they are in our lives.

They sound like flaws in reasoning and as we’ve seen, often they are. But they’re also necessary mental shortcuts our minds take to successfully navigate the world. Our brains don’t have the time, processing power or available data to make perfectly rational and fully researched decisions. So if we’re walking in a dark alley and think we hear footsteps close behind, it’s less costly to quicken our step than assume it’s only the wind.

In sex and relationships, a false assumption about our penis size, sexual skill or attractiveness – all of which we’ve seen that we overestimate – can be the emotional padding we require to date and have sex without imploding with anxiety. But, as we’ve seen, we can also be quick to judge the sex lives of others, assuming they’re a bit less skilled than us and, depending on their appearance, a little kinkier and with more STDs.

The best defense against the dark side of cognitive biases is the knowledge that they’re common to everyone. As neuroscientist David Eagleman advises in his book Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain, “The first lesson about trusting your senses is: don’t. Just because you believe something to be true, just because you know it’s true, that doesn’t mean it is true.”

Methodology

BadGirlsBible.com surveyed 1,013 American men and women (517 women, 496 men) aged 18 to 75 years old in March 2019.

All respondents were self-described as heterosexual and sexually active with a partner of the opposite sex in the last 12 months. As such, the findings should not be generalized to non-heterosexual groups.

Respondents were recruited through online research platform Prolific.co. The platform is designed to enable fast, reliable, and high quality data collection by connecting diverse people around the world. This paper assesses the validity of online crowdsourcing platforms such as Prolific.co by successfully replicating classical cognitive experiments. This paper shows that Prolific.co produces more naïve and less dishonest responses compared to other platforms such as Amazon MTurk.

Respondents were not told the survey was about biases. They were instead told the survey was about their opinions and attitudes towards sex and relationships. As such, it’s possible that some people who were less inclined to talk about sex and relationships may not have chosen to take the survey.

The egocentric bias

Men and women were asked to estimate their erect penis size/their most recent sexual partner’s erect penis size from a list of sizes ranging from 1” to 12” with 0.25” increments. They were not asked about penis girth as it was deemed less likely that men had measured their girth in the past or could accurately estimate their penis circumference compared to its length.

Illusory superiority

Men and women were asked to rate their sexual attractiveness and sexual skill on a scale of 1 to 10 and were explicitly told that 5 represents the average person. Their choice of self-rating relative to the average of 5 is how we determined what proportion believe they’re better looking or more skilled in bed than average.

The halo and horn effects

To analyze the effect of sexual attractiveness on both our perception of sexual skill and the chance someone has had an STD in a way that allowed us to generalize beyond the photos our respondents were shown, we fitted binomial generalized linear models and plotted the fitted lines with 95% confidence intervals from both models.

Stereotyping

To find out whether respondents had stereotyped the people in the photos they were shown, we tested our hypothesis that some photos would be chosen for a fetish significantly more frequently than others. If there was no effect of the faces’ appearances on respondents’ assumptions we would expect each photo to receive an equal share of the votes. The deviation from the equal share is how we assessed the unequal distribution of votes; our proxy for stereotyping.

Illusory correlation

Respondents were given a list of objects to choose from with the option to submit their own answer if a category wasn’t available.

The bandwagon effect

Respondents were asked which of eight sex acts they had participated in at least once. Those who selected acts were then asked if they tried them because they “believed lots of people were doing it” or had seen it in porn. For each act they’d tried, they were also asked how they felt about it in hindsight, with answer options “I strongly wish I hadn’t done it,” “I wish I hadn’t done it,” “No strong feeling,” “Glad I did it,” and “Very glad I did it.” We grouped both regret categories to establish the proportion of people who regretted the act.

The empathy gap

Survey takers were asked if they had ever cheated on any partner in any of five ways ranging from kissing to penetrative sex. To compare the perception of blame and cheating justification, we focused on only those who had either cheated by having penetrative sex with someone other than their exclusive romantic partner and whose partners hadn’t cheated on them to their knowledge, and people who had been cheated on but had never cheated on their partner by having penetrative sex with someone else. When deciding who was to blame, respondents could choose to exclusively select themselves, their partner, someone else, no one at all, other, or any mix of those options. We highlighted those who selected “No one was to blame” in both the cheater and non-cheater groups.

Fair Use Statement

BadGirlsBible.com would love for you to share these findings with the world. Feel free to use the images for non-commercial purposes. All we ask is that you link back to this page to give credit to the research team and readers access to our full findings.If you have any questions about the study or are interested in findings that aren’t included here, please contact [email protected][/otw_shortcode_info_box]

Leave a Reply